‘I quit coaching’: How Packers’ Jeff Hafley found himself in his return to the NFL

The first time Jeff Hafley went out on a limb and took a leap of faith, he was only 26.

The now Green Bay Packers defensive coordinator had a $40,000 job as the defensive backs coach at Albany, and his goal in the spring of 2006 was to learn as much about coaching as possible. Every weekend, he’d find a coaching clinic, jump in his Subaru Outback and drive there, soaking in as much football Xs and Os as he could.

Hafley met Pitt defensive coordinator Paul Rhoads and learned that then-head coach Dave Wannstedt had an open-door policy – where young coaches were welcome to watch spring ball and sit in on meetings. He attended a practice, then the spring game, kept coming back, even working summer camps there.

“I grabbed my defensive coordinator and said, ‘Every time I turn around, this Hafley guy is here,'” Wannstedt told me. “This guy’s a grinder, man. He can’t get enough.”

Wannstedt had an opening on his staff for 2006 and a chance to work with an exceptional player in cornerback Darrelle Revis, but it was only a graduate assistant (GA) job, paying maybe $7,000.

Hafley took the job. He bought an air mattress, and for two years, he slept in his office at Pitt’s football facility. He’d go to dinner with his parents after a home game, and they’d drop him off at the office, joking he had the nicest house in all of Pittsburgh.

“For me, it was like ‘Look, I want to coach.’ I kind of gave up everything, like most coaches do,” Hafley told me. “You don’t really get to see family. You don’t see friends. You lose touch with people. I said I’m going to try to do this until I’m 30 years old, as far as I can. If it works out, I’m going to keep going with it, and if not, then I’ll reassess. I just kept going and never looked back.”

Former Pitt coach Dave Wannstedt took a chance on Jeff Hafley in 2006, with the Packers defensive coordinator working under him as a defensive assistant for five seasons. (Photo by Ned Dishman/Getty Images)

Hafley didn’t even have an apartment, but he was making an impression on everyone around him.

“If we would have a 7:30 staff meeting, I’m in the office around 6, and I’d hear voices,” Wannstedt says. “He’s got our freshmen and all the young defensive backs in a meeting at 6:30 in the morning. There’s nobody in the building, coaches are just coming in and Jeff’s in there having a player meeting. I said to myself, ‘This guy gets it.’”

The humble roots had started earlier, as an oft-injured receiver from Montvale, New Jersey, playing at Division I-AA Siena, which would discontinue its football program three years after he left.

“This was Siena College. You had to really love football to play there,” Jay Bateman, Hafley’s head coach in 2000 and now the defensive coordinator at Texas A&M, told me. “He was such a good teammate, a tremendous worker, loved football. That was a very driven group of kids, and Jeff was one of the leaders of that team.

“As far as being a good receiver? That was questionable, and he’d say the same thing. He’s the typical eye-black, wristbands, go in there to block people and run the right routes every time. But like he wasn’t getting open a whole lot. Just a leader of men, and he’s always been that way.”

When Hafley was pondering leaving Albany for the uncertainty of a GA job and the certainty of sleeping in his office, he called Bateman, asking what he should do.

“Bet on yourself,” Bateman told him. “You have the talent to coach at that level and above. He’s a tremendous football coach. He believes what he believes. I talk to him all the time, and we talk about scheme, but honestly, it’s more about how he’s messaging things to his players. He’ll be a head coach in the NFL soon.”

When Wannstedt resigned after the 2010 season, one of his former assistants, Greg Schiano, called him to ask who his best young coaches were. Schiano hired Hafley to his staff at Rutgers, and a year later, brought him along when he became the Tampa Bay Buccaneers’ head coach.

“I learned so much from Coach Wannstedt, at a young age, on how to be a coach, how to treat people, how to treat a staff, how to communicate with players,” Hafley says. “He probably influenced me more than anyone else on all that stuff. That really helped shape me. [Schiano] He is the most detailed and demanding coach ever. He’s helped me be detailed with my X’s and O’s, dot all my T’s and cross all my T’s. I think it’s a great combination to have these two, because they’re two completely different people. I take something from everyone.”

Hafley went from the Bucs to the Browns for two years, then the 49ers for three years. He had 2-14, 3-13 and 4-12 seasons, with no record in his first seven years as an NFL assistant.

Jeff Hafley joined the 49ers in 2016, working alongside Robert Saleh as San Francisco’s defensive backs coach for three seasons. (Photo by Michael Zagaris/San Francisco 49ers/Getty Images)

But Hafley was fortunate to be surrounded by future NFL coaches. In Cleveland, he worked with Kyle Shanahan, Mike McDaniel, Aaron Glenn, and Kevin O’Connell. With the 49ers, he worked under Shanahan and with Robert Saleh and DeMico Ryans, along with future Ohio State coach Ryan Day.

“It’s all these young people, and we’re picking each other’s brains,” Hafley says. “We talk about football. It’s like heaven, right? All these good people are good coaches. I’ve been around some great staff. … I’ve learned a lot from football just being around Kyle Shanahan. You want to talk about the necessity of knowing what you’re doing and having an answer for what you’re doing, and being able to be confident in what you’re studying in terms of the scheme and the challenge and being in it, if you don’t know what you’re doing around “Kyle, it’s not going to be very good.”

Day hired Halvey to be Ohio State’s defensive coordinator in 2019, beginning his second stint in college football. After a year with the Buckeyes, he became the head coach at Boston College, still only 41 years old. He weathered the COVID-19 pandemic, through the start of the transfer portal and the Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) era, going 22-26 in four seasons, but made a bowl and won in his fourth year.

But Hafley wasn’t really coaching, and he wasn’t really happy.

He told me: “I am a man who loves football and loves coaching, and in the last two years of my life, I no longer coach football.” “I felt like I was doing something else. It was hard for me to leave the team, and it was very hard for me to leave the team, but I wasn’t myself anymore, because I wasn’t doing what I really wanted to do.”

The visibility of the NIL and the threat of player transfers grew with each year at Boston College. Wannstedt spoke regularly with Hafley, and realized how difficult it was to recruit in an uphill battle when other schools in the ACC had larger financial commitments.

“Boston College doesn’t have the resources that Clemson does, and then some,” Wanstedt says. “You work hard to recruit these guys, you train them for a year, you train them for a year, and then they start having success and you can’t afford to keep them. The NIL was just starting to get ready at that time, and some of these teams couldn’t compete.”

Hafley remembers sitting down with receiver Zay Flowers, a future first-round pick, and Flowers was frank with him, telling him that other schools were calling him with offers, tempting him to take more money elsewhere. He convinced Flowers to stay, but it was a sign of everything to come.

“It’s devastating,” Hafley says. “When that keeps happening, over and over again, you’re pouring everything you have into these guys and you’re educating them and training them and you’re probably their only offer, and now they’re probably leaving for the money. They’re not thinking about their degrees and they’re not thinking about their education. So instead of coaching, I’m on the phone trying to raise money.”

Jeff Hafley went 7-6 in his final season at Boston College, leading the Eagles to a bowl win in his final game. A month later, it seemed that he had been demoted in order to find happiness training again. (Photo by John Tlumacki/Boston Globe via Getty Images)

“I got to the point where I said, ‘I don’t want to do this,'” he adds. “I stopped training. I was doing work that wasn’t what I always dreamed of doing.”

Hafley had two years remaining on his contract with Boston College, which reportedly paid him $4 million annually which is close to what top NFL coordinators can make. Packers coach Matt LaFleur reached out to Hafley, who worked with LaFleur’s brother Mike with the 49ers. After their connection, it became clear that a return to the NFL was exactly what Hafley needed.

“I didn’t know what my expectations were, other than that I couldn’t wait to get back to soccer training and immerse myself in soccer again,” Hafley says. “So far, it’s been a lot of fun. Are you asking if this is what I expected? Yes. I love what I do. I love going to work. I love the guys I coach. I love being around the staff. I look forward to it every day.”

Talk to the best players Hafley has coached, and they’ll tell you that one of his strengths is that he will listen to his players, asking them what’s working and what’s not working as he creates a weekly game plan.

“His preparation was amazing,” Richard Sherman, who played for Hafley with the 49ers, told me. “His attention to detail was amazing.” “The most important thing was his ability to communicate with players and have an open ear. Coverage and defense on paper look simple, but there are a lot of nuances to it, and that leads to discussions in the base room. […] He was always a man open to alternative ways of getting the job done and was flexible and open to suggestions. This helped him understand the strengths of his players.”

In 2012, Ronde Barber was 37 years old and playing safety for the first time, and Hafley was 33 years old and his position coach. The Hall of Fame defensive back remembers that he was always “curious,” not because he didn’t know what to do but because he wanted to know what everyone in the room thought. It made him likable, the kind of coach who doesn’t want to disappoint in games.

“He has these quiet leadership qualities that people are drawn to,” Barber told me. “He’s successful because he communicates, and guys know exactly what they’re supposed to do and when they’re supposed to do it.”

The barber continues.

“I’ve watched a lot of Green Bay tape, and they’re not making mistakes. They’re not beating themselves up. It’s on tape, over and over again. He doesn’t have to motivate the players because they’re already motivating themselves because they understand what their jobs are.”

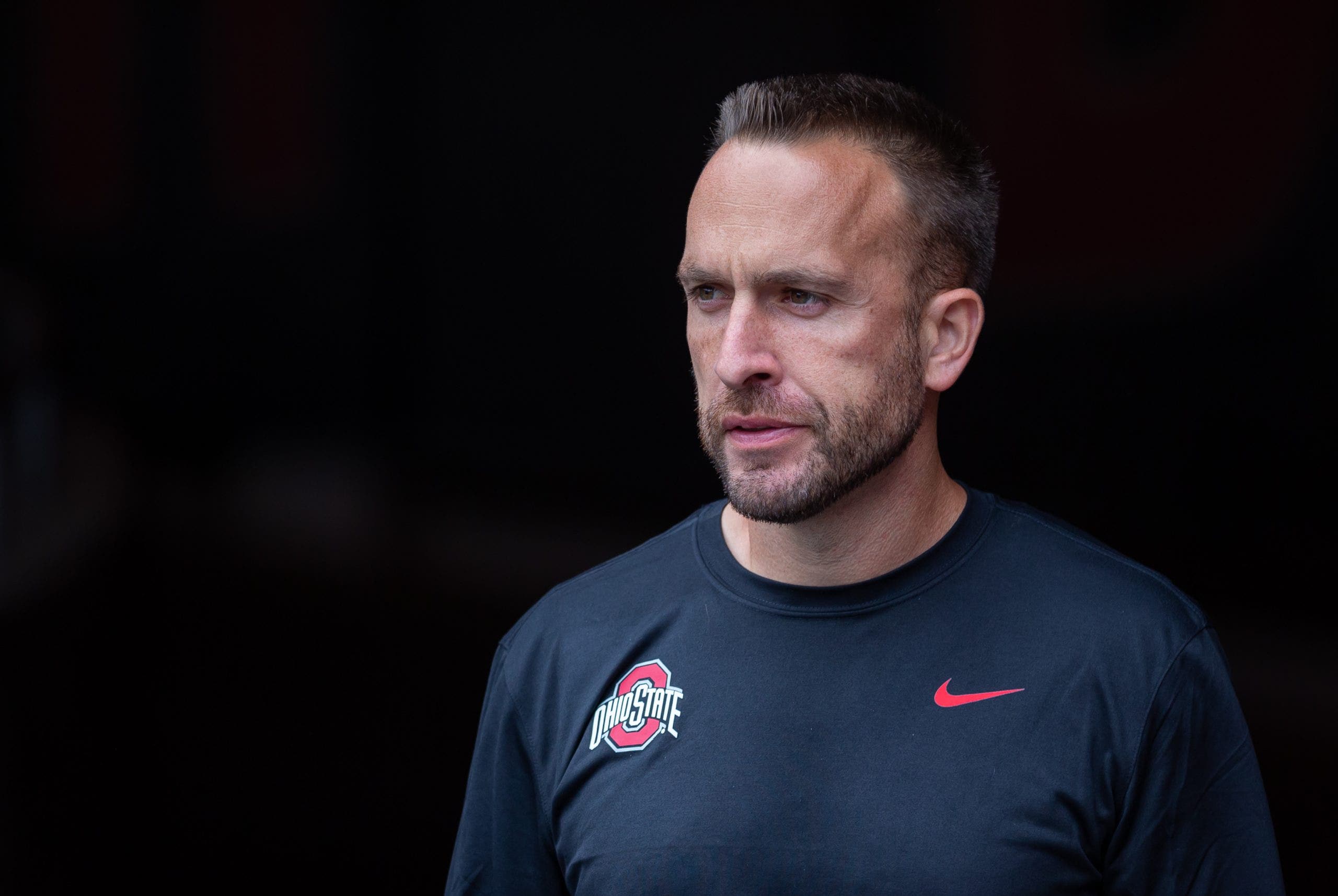

Jeff Hafley’s one season as Ohio State’s defensive coordinator helped elevate the Packers’ defense into one of the best over the past two years. (Photo by Adam Lacey/Ikon Sportswire via Getty Images)

The idea of listening to players and valuing their input began out of necessity for Hafley. His first coaching job was at Division III Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where he was coaching linebackers close to his comfort zone, but when he was hired at Albany, it was coaching defensive tackles.

“I ran into a defensive tackle when I was a fifth-year senior, and I think he was bigger than me at the time,” Hafley says. “I remember calling him and meeting with him. And I said to myself, ‘Look, I don’t even know how to take a stand.’ I’ve played extensively. Let’s sit down, I’ll pick your brain. I coached digital hitting for a year, then I coached outside linebackers for two years, and then I became a base coach, so I learned it from front to back, and I knew I wanted to be a defenseman. “It started with what job I could get, and I ran with it.”

Hafley said he learns from his players every week and will continue to rely on their input when he makes decisions not only about the scheme, but individual game plans from week to week.

“I want to know, if these are the three blitzes, what do you like?” He told me. “If that’s your favourite, guess what? He’ll probably run this blitz well, and maybe take more responsibility with it. ‘Hey, Xavier McKennie, what do you think of this disguise and what it looks like?’ It’s ‘Coach, I like that,’ or maybe let’s have a conversation. Great. Give the players ownership, and if a particular person wants to play a pressing style a little differently, let me know how I can make it better for them.” “For him, instead of changing the whole thing for him.”

Hafley’s career traveling between the college game and the NFL has exposed him to more ideas and challenges. The NFL has a different look from week to week, but nothing like the diversity of ideas and tactics in college football, Sherman said.

“You might get one team that’s completely spread out, where a guy throws it 56 times a game, and then you might get old-school Stanford running the goal line down the middle of the field, boosting the football. And you might make Oregon hustle. You have to adapt to every style of play you get, and that definitely helped him,” Sherman says.

Coaching in college means working with younger players who need more coaching, and he said switching back to the NFL hasn’t changed his awareness that success and development has to start at a very basic level with the players.

“It’s about developing players and teaching these young guys the basics and techniques. I think that’s still the most important thing that people forget sometimes,” Hafley said. “I think in the NFL, people get into scheme, scheme, scheme. Ultimately, I believe with all my heart that it’s about fundamentals and technique. It’s about your eyes and your feet. It’s about getting out of obstacles. It’s about tackling. It’s about leverage. At BC, we didn’t always have the highest-rated recruits. You had to develop players.”

“He’s seen it all. He’s been an assistant, he’s had his own room, he’s been a head coach, and now he can coordinate. The accumulation of all that experience has made him who he is,” Barber says.

Hafley’s first year as NFL coordinator last year was a huge success. The Packers went 11-6, made the playoffs with the youngest team in the league, and Hafley’s defense ranked sixth in points allowed, fifth in yards allowed and fourth in takeaways.

Then, in August, he got a surprise jolt of news. The Packers traded for All-Pro edge rusher Micah Parsons, a move that elevated Green Bay to be viewed as one of the Eagles’ top competitors in the NFC. It’s the kind of move that instantly makes you a better coach, but it also raises expectations of success to a higher level.

Now in his second season as the Packers’ defensive coordinator, Jeff Hafley leads a unit that includes a handful of stars and promising players, including Micah Parsons. (Photo by Larry Radloff/Ikon Sportswire via Getty Images)

“I texted him the other day: ‘I don’t know who your coach is, but I’d like to apply for the job,’” Pittman told me.

Hafley already had confidence in his defense and the Packers as a whole, and the addition of Parsons only added to that.

“I liked our group — last year, by the end of the year, we were at the top of the defense, whatever, five or six,” Hafley says. “You’re building confidence in training camp, getting ready for a season and all of a sudden, one of the elite players in our league comes in at an elite position. He’s been unbelievable with his energy and being a teammate and his coachability. He elevates who we have and what we can do, and he’s brought some extra energy to this group.”

The Packers will play at the Steelers on Oct. 26, so Hafley will return to Pittsburgh, coaching in the same stadium where he worked at Pitt. There is no air mattress now, and he can return home to visit his wife, Jenna, whom he met at Pitt, and their daughters, Hope and Leah.

Hafley coaches at the highest level of football, but he also remembers when he would drive to coaching clinics and sleep in his office. He will now receive a text message from an unknown number, a high school coach with a question about what coverage he wants to run.

“If I’m at Texas A&M High School and I text and say, ‘Hey, do you have five minutes?’ He’ll call me,” Pittman says. “That’s who he is.”

Hafley is always listening and always learning. Even coaches love to be coached.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is that I don’t have all the answers, and if you keep listening and keep learning and growing, things will work out really well,” Hafley says.

Greg Ohman He is an NFL correspondent for FOX Sports. He previously spent a decade covering Pirates to Tampa Bay Times and Sports. You can follow him on Twitter at @gregoman.

Want great stories delivered straight to your inbox? Create or log in to your FOX Sports accountand follow leagues, teams and players to receive a personalized newsletter daily!